How can we make sense of our world, past and present?

Empowered students are able to assess the significance of historical events or processes, and make meaning of evidence across many forms. They ask probing questions of evidence to examine both continuity and change over time, and to assess the causes and consequences of events and actions.

All of this requires students to understand the differences between their perspective and that of others, and uncover the arguments and viewpoints that may be hidden in a source. They use this process to come to conclusions about historical and contemporary events in order to take informed positions and action on relevant issues.

Careful and deliberate instruction is required for students to develop this complex process of historical thinking. It is not enough to ask students to make meaning of source material without explicitly breaking down and scaffolding the nuanced concepts that make up historical thinking. The UC Berkeley History-Social Science Project and others have developed many powerful strategies and models for teaching historical thinking, a few of which are highlighted in this section.

Developing Student Curiosity and Inquiry

How do students learn to ask questions that challenge dominant narratives and uncover missing voices?

Change-makers, especially youth, develop visions for a different world by asking probing questions that often challenge deeply-established assumptions and norms. Especially important are inquiries that seek to elevate voices that are usually absent from the dominant narratives in our society. Our job as teachers includes nurturing and supporting this kind of critical inquiry

RESOURCES - Student Inquiry

- Critical Thinking Cheatsheet (G.Doc)

- Critical Thinking - Question Stems (G.Doc)

- Question Formulation Technique (The Right Question Institute - external site)

Historical Thinking Concepts - The Big Six (+1)

How do we make sense of the past?

Historians have differing understandings of historical thinking. Our work has been informed by The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts, developed by Peter Seixas of the Historical Thinking Project, and influenced through discussion with classroom teachers and colleagues:

-

Historical Significance:How do we decide what is important to learn about the past?

-

Evidence: How do we know what we know about the past?

-

Continuity and Change: How can we make sense of the complex flows of history?

-

Cause and Consequence: Why do events happen, and what are their impacts?

-

Historical Perspectives: How can we better understand the diverse experiences of people of the past and present?

-

The Ethical Dimension: How can history help us to live in the present?

-

The Activist Dimension: How can history help us work towards equity and justice? (#7 was added by our colleagues at the UCLA History-Geography Project)

RESOURCES - Historical Thinking Concepts & Guideposts

-

The Big Six + 1 Historical Thinking Concepts & Guideposts: The seven concepts are broken down into Guideposts that explore the nuances of the concept. (PDF)

-

Asking Critical Questions of the Construction of History: This offers a starting point to challenge and expand the Big Six Concepts & Guideposts by asking critical questions about how history is constructed - Ethnic Studies and land-based pedagogical frameworks can be used to expand our approach to Historical Thinking. (G.Doc)

Scaffolding Historical Thinking Skill Development

How can teachers explicitly break down and scaffold the skills of historical thinking and analysis?

Teaching Historical Thinking requires teachers to isolate and explicitly teach the various concepts. Some of the scaffolds below focus on introducing or reinforcing a single guideposts, others are reading strategies through the lens of a particular historical concept.

As students develop these specific skills, they are more able to integrate the concepts and engage in deep Historical Thinking as they examine history and our contemporary world.

RESOURCES - Scaffolds for Historical Thinking Skills

Here is a selection of Historical Thinking strategies and scaffolds. Unless otherwise noted, these links go to entries in the UCBHSSP Instructional Strategies Database.

- Significance

- Introducing the concept of Historical Significance

- Significance and Timelines

- Evidence

- Introducing the concept of Evidence

- Evidence, Analysis and Reasoning

- Primary Source Analysis

- Continuity & Change

- Introducing the concept of Continuity and Change

- Assessing Progress & Decline - Timeline

- Cause and Consequence

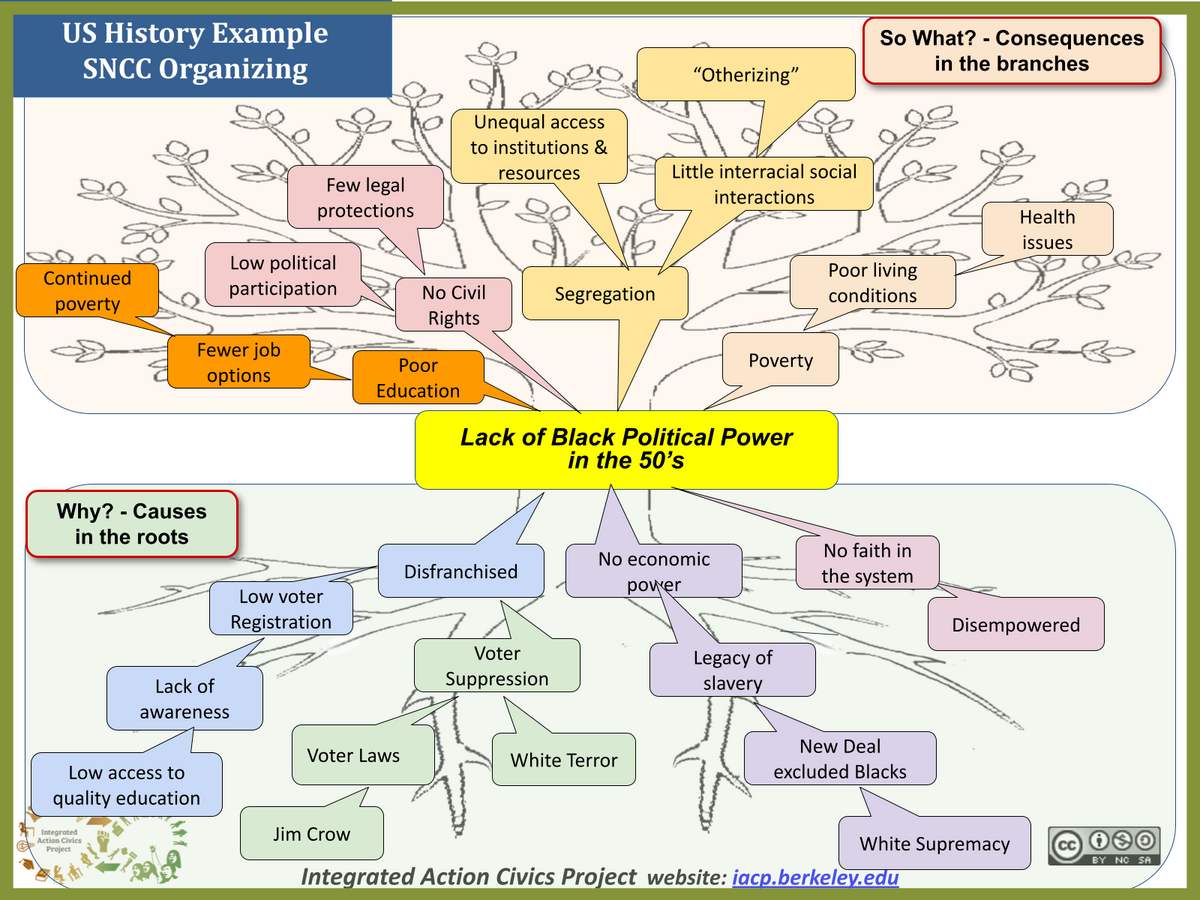

- Why and So What - Causes and Consequences Tree

- Reading for Cause and Consequence

- Perspective

- World View - How we develop our views and opinion

- Stakeholder Analysis

- Ethical Dimension

- Interrogate the Source: Hidden arguments / Passive Voice (G.Doc)

- Rigged Monopoly - Rectify historical inequities (UCBHSSP Lesson Database)

- Making History - Local history and response (UCBHSSP website)

- Activist Dimension

- See Change-Analysis Section

- Analyze the Message - Exploring how awareness is developed (G.Doc)

- Building Awareness - Student messaging - scaffolded (G.Doc)

Change Analysis Strategies in Historical Analysis

How can change analysis strategies be applied to course content to help students both master these skills and make sense of history?

The Change Analysis strategies provide powerful lenses with which to understand the process of social struggle and change in history. It is important for students to not only learn that change took place, but also how changes occurred. This requires investigating root causes, the complex dynamic of power, the role of different stakeholders, and the strategies and tactics used to work toward a more just society.

Many of these strategies, applied to course content, asks students to examine primary and secondary sources to learn how leaders and community members shaped the movements and events in history. Examples of these are shared throughout the Change Analysis module.